In Māori, rimu denotes both the tree Dacrydium cupressinum, and also functions as a generic name for mosses, lycopods ("club mosses") and seaweeds.

Although the word itself is derived from an ancient generic term for mosses, algae and seaweeds, a meaning which is present in most cognate words in other languages, and is retained also in Māori, it is not hard to see why its meaning was extended to the rimu tree, whose foliage does look as if it would be equally appropriate on an underwater plant, or as the form of a soft coral (which is one of the meanings of the word in Hawaiian).

The rimu is a tall forest tree, growing from 20-30 metres or higher, which was used in the manufacture of weapons, especially heavy-duty long spears, and for a variety of medicinal purposes. The foliage of young trees reminiscent of a feathery seaweed, hence its name. Its small seed (about 3mm long) is borne on a succulent, red recepticle (illustrated on the left). The fruits ripen in the autumn, but the tree usually fruits only once every three or four years. Large stands of rimu once dominated the forest in many parts of the North Island. After European settlement

its exceptionally strong, durable and attractive timber became a major source for the frames and weatherboarding of houses and for making high-grade furniture -- rimu furniture is still highly esteemed, but strict conservation measures

are now in force because of the gross over-exploitation of this resource. In the past, practically every part of the tree has had important uses -- Murdoch Riley notes that Captain Cook's crew used rimu branchlets mixed with mānuka twigs and molasses to make

a beer (Herbal, p. 420), and

more recently they have been used to clarify and flavour home brew. The red sap is said to have come from the blood of Tunuroa, a dreaded water monster (ibid.). The rimu is a tall forest tree, growing from 20-30 metres or higher, which was used in the manufacture of weapons, especially heavy-duty long spears, and for a variety of medicinal purposes. The foliage of young trees reminiscent of a feathery seaweed, hence its name. Its small seed (about 3mm long) is borne on a succulent, red recepticle (illustrated on the left). The fruits ripen in the autumn, but the tree usually fruits only once every three or four years. Large stands of rimu once dominated the forest in many parts of the North Island. After European settlement

its exceptionally strong, durable and attractive timber became a major source for the frames and weatherboarding of houses and for making high-grade furniture -- rimu furniture is still highly esteemed, but strict conservation measures

are now in force because of the gross over-exploitation of this resource. In the past, practically every part of the tree has had important uses -- Murdoch Riley notes that Captain Cook's crew used rimu branchlets mixed with mānuka twigs and molasses to make

a beer (Herbal, p. 420), and

more recently they have been used to clarify and flavour home brew. The red sap is said to have come from the blood of Tunuroa, a dreaded water monster (ibid.).

The rimu tree is mentioned in Himiona Kaamira's account of the discovery of Aotearoa by Kupe. When Kupe had returned to Hawaiki, his protegé Nukutawhiti made a return voyage to Aotearoa, and immediately they reached the shore he recited appropriate karakia to assure the security of the waka and its passengers, before landing and going ashore alone to collect some rimu shoots:

Mutu ake ngā karakia a Nuku-tawhiti, ka ū tō rātou waka. Ka mea atu a Nuku-tawhiti ki tōna iwi, “Noho mārire i runga i te waka.” Ka haere a Nuku-tawhiti, ka katohia mai e waru ngā pītau-rimu. Ka mauria mai, ka hoatu ki ngā taniwha e whā ngā pītau, Ka hoatu ki a Puhi-moana-ariki rāua ko Rangi-uru-hinga e rua. Ka mea atu ia, “Mauria ēnei pītau mā kōrua e hoatu ki a Kupe, māna e panga atu ki Moana-ariki teretere ai, hei tohu whakamaharatanga ki a au.” Ka mea atu ia ki a Ara-i-te-uru rāua ko Niua, “Ko ēnei pītau e rua e here i a kōrua ki Hokianga, hei tohu whakamaharatanga mā kōrua ki a au, hei whakaako mā kōrua ki aku whakatupuranga i muri i a au.” Ka hoatu e ia e rua ngā pītau ki ngā atua, ki a Te Hiko-o-te-rangi, ki a Mahere-tuki-te-rangi. Ka mea atu ia, “ Ko ēnei pītau e rua mā kōrua e mau atu ki a Tohi-a-rangi i runga nei, māna e mau atu ki Te Moana-Wairua i runga nei teretere ai, hei whakamaharatanga i muri i a au.” Ka ingoatia ērā pītau ko Te Kāhui-ao, ko Te Kāhui-pō. Ka tae ia ki ngā pītau e rua, ka mea atu ia ki ngā taniwha, ki ngā atua, ki ngā tāngata hoki. “Ko ēnei pītau e rua ka whiua e ahau ki uta nei, ki reira rāua noho whakapuna a waru ai, hei pupuri i te arikitanga.

Ka ingoatia tētahi o ēnei pītau ko Taku-heke-tahuhu, ka ingoatia tētahi ko Taku-heke-takere, o Te Kāhui-ao, o Te Kāhui-pō. Ka mutu ngā kōrero. Ka mihi atu ia ki a Puhi rāua ko Rangi-uru, ka hokihoki a Te Hiko, rāua ko Mahere. Hoki tahi atu ana rātou ki Hawaiki-rangi.

I muri i a rātou ka haere a Nuku-tawhiti ki uta, ki te kawe i ngā pītau rimu e rua, he whakaau mo rātou ki te whenua. I muri i te otinga o tērā mahi kātahi ano ngā tāngata ka haere atu ki uta.

When the spells of Nuku-tawhiti ended their canoe reached land. He went and plucked eight rimu shoots and brought them and gave four of them to the sea demons. He gave two to Puhi-moana-ariki and Rangi-uruhinga, and said, “You two take these shoots and give them to Kupe. He will cast them on the Chiefly-sea to float as a remembrance of me.” He said to Ara-i-te-uru and Niua,“These two shoots will bind you to Hokianga, as a sign of remembrance for you of me, to be shown by you to my descendants after me.” He gave two of the shoots to the gods Te Hiko-o-te-rangi and Mahere-tuu-ki-te-rangi. He said, “These two shoots are for you, for you to take to Tohi-a-rangi above, who will take them to Te Moana-wairua (the Spirit-sea) above, to float there as a sign of remembrance after me. Those shoots were named Kāhui-ao and Kāhui-pō. He took two shoots and said to the sea-demons, and to the immortals, and to the people, “I will throw these two shoots onto the land, where they will remain as the plant called whakapuna-a-waru, to preserve the chiefly prestige.

One of the shoots was called Taku-heke-tāhuhu and the other was called Taku-heke-takere, of the Kāhui-pō, of the Kāhui-ao. So ended the talk. He greeted Puhi and Rangi-uru, and the immortals. So Puhi and Rangi-uru, and Te Hiko and Mahere returned. They went back together to Hawaikirangi.

After they went Nuku-tawhiti went ashore to take the two rimu shoots, as a sign confirming their presence in the land. After that task was completed then at last the people went ashore.

-- Kupe, by Himiona Kaamira, Journal of the Polynesian Society, Vol. 66, No. 3 1957; translation by Bruce Biggs.

Puakarimu

An alternative name for rimu tree in the Rotorua area is puaka. This would seem to be related to the name puakarimu (which came first is a matter of conjecture), denoting a lycopod, Pseudolycopodium densum (formerly known as Lycopodium deuterodensum), which itself looks very like either a seedling rimu tree, or a land-based feathery seaweed. This plant is often found on the forest floor, growing especially among stands of mānuka and kānuka.

There are some excellent photos of the puakarimu on the NZ Flora web site (click on the "Taxon" link for more information and images), and also on the NZPCN website; one from the latter source, taken by Jeremy Rolfe, is reproduced in the gallery below. The resemblance to a rimu seedling is unmistakable.

Rimurapa

The rimurapa is the ubiquitous bull kelp, common on rocky shorelines and washed up on beaches throughout Aotearoa, and probably what comes to mind first when "seaweed" is mentioned. It is also found in Chile, Argentina, Norfolk Island and Antartica, and its long tresses are said to form the gateway to Te Reinga, the Underworld. The plant is mentioned in a poignant lament published with an interlinear translation by Haare Hongi in an early issue of the Journal of the Polynesian Society, a portion of which is reproduced here (macrons and italics added):

Ka paea Potoru ki te au o Raukawa.

Raukawa's current beats Potoru's prow,

Ka eke i tō ranga ki Otama-i-ea,

On Tama-i-ea's sand-banks he rests—alas!

He maunga rimu-rapa e tū noa mai rā,

A lone and cheerless isle where sea-weeds cling,

I tai te tārawa haerenga kaipuke,

In far mid ocean; there huge vessels pass,

Nāna i hōmai te Paea-o-Tawhiti,

And subtle flints from distant countries bring,

Hei whakatuohotanga ki te iwi ka ngaro.

To waste the people now, alas, too few.

("Lament over a fallen warrior chief", JPS 2 (2), June 1893, p. 122). This appears to be a contribution from Haare Hongi, but the only information about its provenance is the note that "The composer of this lament was himself slain half a century ago" -- possibly also a victim of the "subtle flints" brought by the ocean vessels to waste the people.

Schedule 97 of the Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998 recognizes the rimurapa (Durvillaea antarctica) as a taonga species for the iwi. It is listed as a non-commercially harvested species under s. 306 of the Act, and is protected from commercial harvesting within the iwi traditional seafood harvesting grounds.

Rimurehia

The rimurehia, identified in the Williams' Dictionary as the seaweed Zostera novaezelandica (illustrated on the left; now known as Z. muelleri subsp. novaezelandica), also appears in ancient Maori narratives -- in this case in accounts of the exploits of the culture hero Māui. Murdoch Riley identifies the name instead with seaweeds of the genus Gigartina (the group from which carageen is obtained). Either would fit in with the Māui narrative. One species or Gigartina, from the Bay of Islands, is illustrated in the gallery at the end of this page. The rimurehia, identified in the Williams' Dictionary as the seaweed Zostera novaezelandica (illustrated on the left; now known as Z. muelleri subsp. novaezelandica), also appears in ancient Maori narratives -- in this case in accounts of the exploits of the culture hero Māui. Murdoch Riley identifies the name instead with seaweeds of the genus Gigartina (the group from which carageen is obtained). Either would fit in with the Māui narrative. One species or Gigartina, from the Bay of Islands, is illustrated in the gallery at the end of this page.

According to the account in Ngā Mahi ā ngā Tūpuna, Māui's father warned him of the danger of conflict with Hine-nui-te-Pō, but Māui was determined to seek her out. The account continues:

Kātahi ia ka mea atu, "He pēwhea tōna āhuatanga?"

Ka mea ia, "Te mea e kōrapu mai rā ko ōna mata; ko ōna niho kei te koi mata; ko te tinana he tangata anō; engari ngā karu he pounamu; ko ngā makawe i rite ki te rimurehia; ko te waha i rite ki te manga." (p. 22, macrons added)

Then Māui asked his father, “What is my ancestress Hine-nui-te-pō like?” and he answered, “What you see yonder shining so brightly red are her eyes, and her teeth are as sharp and hard as pieces of volcanic glass; her body is like that of a man; and as for the pupils of her eyes, they are jade (pounamu); and her hair is like the tangles of long seaweed, and her mouth is like that of a barracouta.”

Māui ignored his father’s advice, and, as predicted, met his doom.

(There is an interesting commentary in this text: "What does Hine-Nui-te-Pō look like? A case study of oral tradition, myth and literature in Aotearoa New Zealand", by Simon Ferris, in the Journal of the Polynesian Society Vol. 174, No. 4, December 2018, pp 365-388.)

The Zostera sp. is also known as "eel grass" or "sea grass". It is a plant of the mudflats and shallow sandy-silt shore margins, with creeping rhizomes and narrow, grass-like leaves 5-30 cm long. It is a herb (family Zosteraceae) rather than a true seaweed. The plants of the genus Gigartina are however definitely marine algae (family Gigartinaceae), with more than a dozen species known from New Zealand. The one illustrated in the gallery, G. alveata, was photographed on a reef in the mid intertidal zone near Long Beach, Russell, in the Bay of Islands.

Murdoch Riley (Herbal, p. 415) notes that the Gigattina seaweed was mixed with the berry-like petals of the tutu, or with konini (Fuchsia excorticata) berries, to make a “thick, nutritious jelly”, eaten cold. The fronds are extremely long lasting when washed after collection, dried in the sun and stored in flax baskets. European settlers also adopted these plants as a food.

A “carrageen custard” can be made by adding butter, one ot two beaten eggs, sugar to taste and vanilla or almond essence to the rehia. Serve with stewed fruit.

Rimu in Te Paipera Tapu

In Te Paipera Tapu "rimu" appears as the name both for a noble forest tree, and for a seaweed, reflecting well the word's Proto Malayo Polynesian ancestry.

In Isaiah 41:19, and again in Isaiah 60:13 "rimu" has been used to translate Hebrew tidhar, a puzzling word for which scholars are still trying to locate a precise modern referent. It is rendered variously as "pine, "plane" or "cypress" in English transations, but Michael Zohary (Plants of the Bible, p.112) thinks that the evidence points to the Laurestinus, Viburnum tinus. In the Samoan version, an approximation of the Hebrew word is used. This is a leafy shrub or, in Palestine, a small forest tree, now widely cultivated as an ornamental shrub, growing 2-7 metres high, with fragrant clusters of white flowers followed by shiny metallic black berries. In Isaiah 41:19, and again in Isaiah 60:13 "rimu" has been used to translate Hebrew tidhar, a puzzling word for which scholars are still trying to locate a precise modern referent. It is rendered variously as "pine, "plane" or "cypress" in English transations, but Michael Zohary (Plants of the Bible, p.112) thinks that the evidence points to the Laurestinus, Viburnum tinus. In the Samoan version, an approximation of the Hebrew word is used. This is a leafy shrub or, in Palestine, a small forest tree, now widely cultivated as an ornamental shrub, growing 2-7 metres high, with fragrant clusters of white flowers followed by shiny metallic black berries.

Ka whakatokia e ahau te koraha ki te hita, ki te kōwhai, ki te ramarama, ki te rākau hinu; ka tū i ahau te kauri ki te titohea, te rimu, ratou tahi ano ko te ake. [Ihaia 41:19]

I will plant in the wilderness the cedar, the shittah tree, and the myrtle, and the oil tree; I will set in the desert the fir tree, and the pine, and the box tree together: [KJV]

I will put in the wilderness the cedar, the acacia, the myrtle and the olive; I will set in the desert the cypress, the plane and the pine together. [NRSV]

Isaiah 60:13 is translated the same way:

Ka tae mai te kororia o Repanona ki a koe, te kauri, te rimu, me te ake ngatahi hei whakapaipai, mo te wahi i toku kainga tapu ....

The glory of Lebanon shall come unto thee, the fir tree, the pine tree, and the box together, to beautify the place of my sanctuary .... [KJV]

The glory of Lebanon shall come to you, the cypress, the plane and the pine, to beautify the place of my sanctuary .... [NRSV]

E ō mai ‘iā te oe mea e ta‘ua ai Lepanona,

o le perosi ma le titara ma le tasura e fa‘atasi. [PT]

"Rimu" makes its third appearance in Māori Biblical translation in Jonah 2:5, where it represents the Hebrew suf -- the taxon for water plants, probably from the context not referring to any one in particular. Not surprisingly, the Samoan translation uses the word limu in this context.

Karapotia ana ahau e te wai, tae tonu ki te wairua; i oku taha katoa te rire a a taka noa; he rimu o taku mahunga.

The waters compassed me about, even to the soul: the depth closed me round about, the weeds were wrapped about my head. [KJV]

The waters closed in over me, the deep surrounded me; weeds were wrapped around my head. [NRSV]

‘Ua si‘osi‘oina a‘u e le sami,

na manū a‘u oti;

‘ua ufitia a‘u i le moana,

‘ua fusia lo‘u ulu i le limu. [TP]

*Limu

PROTO-POLYNESIAN, from PROTO OCEANIC *limut, "Generic name for moss, algae and seaweeds;" probably a fusion of PROTO MALAYO-POLYNESIAN *limu "moss" and *lumut "moss, lichens"

RELATED WORDS IN OTHER AUSTRONESIAN LANGUAGES

(Reflexes in Polynesian languages are listed at the top of the page.)

Ilokano (Philippines): limu "seaweed", lumot "moss, some algae, and river weeds"

Tagalog (Philippines): limu "seaweed", lumot "moss, some lichens"

Ifugao (Philippines): lumuy "various lycopods and lichens"

Javanese (Indonesia): lumut "moss, seaweed"

Hova (Madagascar): lumutra "moss, seaweed"

Reflexes of Proto-Oceanic variant *lumut

Lou (Admiralty Islands): lum "seaweed; grass or weed growing in water"

Trukese (Micronesia): rūm "seaweed, moss, algae"

Rotuman: lumu "seaweed, moss"

Reflexes of Proto-Oceanic variant *limut

Kara (Papua New Guinea): limut "tree moss"

Marshallese (Micronesia): limulimu "moss"

Judging by the evidence from Western Malayo-Polynesian languages, Malcolm Ross (Proto Oceanic Lexicon, Vol 3, pp. 76-7) suggests that two separate Proto Malayo-Polynesian words, *limu "seaweed" and *lumut "moss" may have been fused into a single word, reconstructed as * limut, in Proto Oceanic, and used as a generic term for mosses, algae and seaweeds. (The word *lumut is reflected unchanged in many contemporary Philippine languages, meaning "moss"; terms for "seaweed" vary widely; *limu has also been retained, unchanged, in a few languages like Ilocano and Tagalog, as a word primarily indicating mosses. Lumot on the other hand has a wider range, including, for example, certain lichens, like the lumot-kahoy "tree-borne lumot", Usnea philippina, illustrated in the gallery below), and in Tagalog, Ilocano and the Bisayan languages refers in particular to certain species of "sea lettuce", particularly Ulva intestinalis (also illustrated in the gallery). The fusion of *limu and *lumot probably happened early in the history of the language, as most Austronesian languages reflect only one variant or the other. Judging by the evidence from Western Malayo-Polynesian languages, Malcolm Ross (Proto Oceanic Lexicon, Vol 3, pp. 76-7) suggests that two separate Proto Malayo-Polynesian words, *limu "seaweed" and *lumut "moss" may have been fused into a single word, reconstructed as * limut, in Proto Oceanic, and used as a generic term for mosses, algae and seaweeds. (The word *lumut is reflected unchanged in many contemporary Philippine languages, meaning "moss"; terms for "seaweed" vary widely; *limu has also been retained, unchanged, in a few languages like Ilocano and Tagalog, as a word primarily indicating mosses. Lumot on the other hand has a wider range, including, for example, certain lichens, like the lumot-kahoy "tree-borne lumot", Usnea philippina, illustrated in the gallery below), and in Tagalog, Ilocano and the Bisayan languages refers in particular to certain species of "sea lettuce", particularly Ulva intestinalis (also illustrated in the gallery). The fusion of *limu and *lumot probably happened early in the history of the language, as most Austronesian languages reflect only one variant or the other.

When in Hawaii I came across a photograph of a Hawaiian seaweed that made the extension in Aotearoa of this name to include the rimu tree (Dacrydium cupressinum) seem a highly logical choice, but I neglected to note the source. However, I did find a photograph of a Hawaiian moss, reproduced in the next paragraph, which is highly reminiscent of Aotearoa's rimu tree, and also an article on the Singaporean "Wild Singapore" web site about the feathery green seaweeds, some of which, at first glance, bring into mind the foliage of trees like the rimu. The one illustrated above, Caulerpia taxifolia, has yew-like "leaves", reflected in its botanical specific name, taxifolia, meaning "yew-like foliage", which in Aotearoa it shares with the miro. This species obviously reminded the botanist who gave it its scientific name of a tree. In Tongan and Hawaiian, as well as probably many other Polynesian languages -- and probably Austronesian languages generally, related words also refer to some species of fern. In Tonga limu applies particularly to the epiphytic "whisk fern" Psitotum nudum (pictured on the right), a small epiphyte found throughout the tropical Pacific. When in Hawaii I came across a photograph of a Hawaiian seaweed that made the extension in Aotearoa of this name to include the rimu tree (Dacrydium cupressinum) seem a highly logical choice, but I neglected to note the source. However, I did find a photograph of a Hawaiian moss, reproduced in the next paragraph, which is highly reminiscent of Aotearoa's rimu tree, and also an article on the Singaporean "Wild Singapore" web site about the feathery green seaweeds, some of which, at first glance, bring into mind the foliage of trees like the rimu. The one illustrated above, Caulerpia taxifolia, has yew-like "leaves", reflected in its botanical specific name, taxifolia, meaning "yew-like foliage", which in Aotearoa it shares with the miro. This species obviously reminded the botanist who gave it its scientific name of a tree. In Tongan and Hawaiian, as well as probably many other Polynesian languages -- and probably Austronesian languages generally, related words also refer to some species of fern. In Tonga limu applies particularly to the epiphytic "whisk fern" Psitotum nudum (pictured on the right), a small epiphyte found throughout the tropical Pacific.

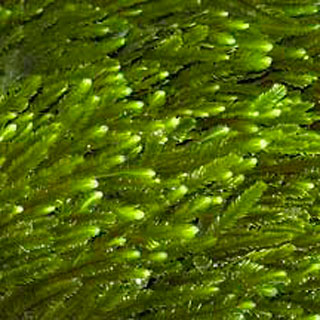

In Hawaii the reflex limu is used to refer to mosses, like the one (species unknown) illustrated on the left, lichens and all plants growing submerged in both fresh and salt water, and includes also soft corals; the expression limu pae "seaweed washed ashore" is used denote a somewhat unwelcome wanderer. Interestingly, in Rapanui the primary meaning of rimu seems to be to cut up or grind, and secondarily a particular kind of seaweed when when it has been washed up on the shore and dried out. In Tuamotuan, a secondary meaning of rimu, according to the Stimson dictionary, is "moss-like hair" -- unfortunately, this definition is not made more explicit or illustrated (but see the description of Hine-nui-te-Pō in the section on Māori rimurehia, above!). In Hawaii the reflex limu is used to refer to mosses, like the one (species unknown) illustrated on the left, lichens and all plants growing submerged in both fresh and salt water, and includes also soft corals; the expression limu pae "seaweed washed ashore" is used denote a somewhat unwelcome wanderer. Interestingly, in Rapanui the primary meaning of rimu seems to be to cut up or grind, and secondarily a particular kind of seaweed when when it has been washed up on the shore and dried out. In Tuamotuan, a secondary meaning of rimu, according to the Stimson dictionary, is "moss-like hair" -- unfortunately, this definition is not made more explicit or illustrated (but see the description of Hine-nui-te-Pō in the section on Māori rimurehia, above!).

|