|

The narrative portion of this page is divided into four sections:

Introduction;

Are Manuka, Maanuka and Mānuka different words?;

Is Mānuka still a Maori word?;

Mānuka in proverbs and poetry;

Manuka honey.

These are followed by references and suggestions for further reading, and acknowledgements.

Introduction

The most widely used names for this group of trees may be derived ultimately from the Proto-Austronesian word root *nuka ("wound"), which gave rise to the Proto-Polynesian plant name *nukanuka, referring to the tree Decaspermum fruticosum (Myrtaceae), related and similar in appearance to the trees called mānuka in Aotearoa. A similar tree, D. vitiense the "Fijian Christmas tree", is found in Fiji, with the cognate name nuqanuqa. The name has been reduced to the basic word root (nuka) in Māori and further modified with the formative prefixes mā- and ka-. The origin of these plant names is discussed in the page about the Proto-Polynesian word root (see the link at the top of this page). Because of the multiplicty of names and overlapping meanings, there are five separate pages in this set: (1) Proto-Polynesian *nukanuka, with its antecedents and reflexes; (2) the Māori word mānuka in its own right (this page); (3) mānuka in the form of members of the genus Kunzea, a.k.a. kānuka; (4) mānuka in the form of species and varieties until recently grouped together as Leptospermum scoparium, a.k.a. kahikātoa; (5) mānuka rauriki in the form of Leucopogon fasciculatus, a.k.a. mingimingi (mānuka rauriki is also an alternative name for some of the Kunzea species). In Taitokerau (Northland), mānuka is the preferred name for Kunzea species; elsewhere these are most commonly referred to as kānuka. When there is a need to refer explicitly to Leptospermum scoparium (s.l.) plants, kahikātoa is the preferred Northern term, and mānuka has this function elsewhere. The most widely used names for this group of trees may be derived ultimately from the Proto-Austronesian word root *nuka ("wound"), which gave rise to the Proto-Polynesian plant name *nukanuka, referring to the tree Decaspermum fruticosum (Myrtaceae), related and similar in appearance to the trees called mānuka in Aotearoa. A similar tree, D. vitiense the "Fijian Christmas tree", is found in Fiji, with the cognate name nuqanuqa. The name has been reduced to the basic word root (nuka) in Māori and further modified with the formative prefixes mā- and ka-. The origin of these plant names is discussed in the page about the Proto-Polynesian word root (see the link at the top of this page). Because of the multiplicty of names and overlapping meanings, there are five separate pages in this set: (1) Proto-Polynesian *nukanuka, with its antecedents and reflexes; (2) the Māori word mānuka in its own right (this page); (3) mānuka in the form of members of the genus Kunzea, a.k.a. kānuka; (4) mānuka in the form of species and varieties until recently grouped together as Leptospermum scoparium, a.k.a. kahikātoa; (5) mānuka rauriki in the form of Leucopogon fasciculatus, a.k.a. mingimingi (mānuka rauriki is also an alternative name for some of the Kunzea species). In Taitokerau (Northland), mānuka is the preferred name for Kunzea species; elsewhere these are most commonly referred to as kānuka. When there is a need to refer explicitly to Leptospermum scoparium (s.l.) plants, kahikātoa is the preferred Northern term, and mānuka has this function elsewhere.

This page deals pimarily with the word mānuka, which may be spelt mānuka, maanuka, or manuka; the plants to which it refers are discussed in more detail in the pages for kānuka (Kunzea ericoides s.l.) and kahikātoa (the New Zealand variants of Leptospermum scoparium s.l.), some of which are now recognized as separate species. (The abbreviation s.l. by the way, denotes sensu lato, "in a broad sense"; i.e. broadly speaking, as against s.s. sensu stricto "in a concise sense", i.e. strictly speaking, so in this context Kunzea ericoides s.l. can be interpreted as meaning "the groups of related plants that used to be labelled collectively as Kunzea ericoides", and Kunzea ericoides s.s. as "the plants now classified as Kunzea ericoides". If you follow the links to Kānuka and Kahikaatoa, you will find the difference exemplified.

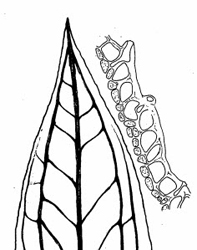

You can tell the Kunzea from the Leptospermum species apart by the larger flowers of the latter, and their slightly larger leaves which are also more pointed and prickly than those of the Kunzea species. If you have a microscope (or a very powerful magnifying glass) handy you can separate out the kānuka (Kunzea) from the kahikātoa (Leptospermum) species of mānuka by investigating the margins of the leaves. The botanist Rhys Gardiner discovered that the apparently smooth leaf edges of the Leptospermum leaves had minute serrations, although these were only visible at magnifications of x10 or higher. The Kunzea leaf margins on the other hand were smooth, even at this magnification. Furthermore, when the soft tissue was dissolved to expose the veins, he found that the arrangement of the veins in the Leptospermum leaves was symetrical and the veins converged right at the tips of the leaves (which helps to explain their strongly aromatic quality). The veins in the Kunzea on the other hand were tangled, and did not reach right to the leaf tip. Portions of the sketches illustrating his paper "Notes towards an excursion flora" (2002) are reproduced below.

Leaf tip of Leptospermum scoparium, showing symetrical arrangement of the veins, extending to leaf tip, and minute serrations on the leaf edges.

(Source: Rhys Gardener, "Notes Towards an Excursion Flora: Manuka Leptospermum scoparium Myrtaceae")

|

Leaf tip of Kunzea sp. (Kānuka), showing the smooth leaf edges and the tangled arrangement of the veins, which do not reach right to the leaf tip.

(Source: Rhys Gardener, "Notes Towards an Excursion Flora: Manuka Leptospermum scoparium Myrtaceae") |

Are Manuka, Maanuka and Mānuka different words?

There are three ways of spelling "mānuka".

The first, "manuka" -- six characters, no diacritical marks -- was the normal spelling for 150 years for Māori and non-Māori alike. The second, maanuka, repeating the first vowel character to indicate that the first vowel sound is lengthened, might occasionally have been used to indicate the correct pronunciation of the word, and the spelling mānuka, with a macron to mark the lengthened vowel, was found in scholarly and academic works like the Williams Dictionary and some educational materials. In writing in English, until very recently the standard spelling has been "manuka", now often corrected to "mānuka" to conform to the standard for written Māori laid down by the Māori Language Commission. This may also help English speakers, who often pronounce the word with a short first vowel and long, stressed middle one, as if it were written manūka, to align their pronunciation closer to the Māori standard (where the stress is on the lengthened initial vowel). All three spellings and the different pronunciations are simply variant representations and articulations of the same word.

The use of a repeated -- "double" -- vowel characters was long a customary way of denoting vowel length when there was likely to be confusion, but it was rarely used to write words like "mānuka" until the late Professor Bruce Biggs promoted the use of this device to mark inherent vowel length in written Māori generally, to help ensure that learners and people unfamiliar with the language would be able to pronounce Māori words correctly and distinguish among words which differed only in the length of one or more of the vowels. When he developed this system in the 1950s and 60s this was also a practical approach, as most typewriters did not come equipped with macrons or other diacritics, and later the first word-processing programs did not have fonts in which macronized characters were standard. The doubled vowels also reflected part of the history of the language, as most long wowels have resulted from the loss of a consonant between two, usually identical, vowels.

The use of the macron dates back almost to the beginnings of written Māori, and was used for all headwords containing long vowels in the various editions of the authoritative Williams Dictionary. Until Professor Biggs advocated the use of double vowels, it was also the standard way of marking vowel length in academic writing. The Education Department's Advisory Committee on the Teaching of the Maori Language, which was responsible for producing the seventh edition of the Williams Dictionary, retained the use of the macron in that work, and made it the standard for use in educational materials.

This policy was continued by the Māori Language Commission, established in 1987, and became the standard Māori orthography. The introduction of macronized fonts in widely used computer programs, and the demise of the typewriter reduced the practical advantages of Professor Biggs' system, which now has widespread use only among supporters of the Tainui Kīngitanga, reflecting the influence of the late Sir Robert Mahuta, the Tainui Chief Negotiator who had been a student of Professor Biggs at the University of Auckland.

Just as the rose by any other name would smell as sweet, mānuka, however the name is written or pronounced, remains essentially the same word. Variations in spelling or pronunciation

do not alter its referent, in relation to honey the endemic New Zealand varieties of Leptospermum scoparium, and more generally in some parts of the country, when not referring to honey, widened to include endemic New Zealand species of the genus Kunzea (otherwise known as Kānuka).

The different ways of writing and articulating this word do not affect its meaning.

Is Mānuka (still) a Māori word?

The word mānuka has links to tropical Polynesia, but in its current form it is probably unique to te reo Māori (see the page on the Proto-Polynesian antecedents of this name for more detail). The entry for manuka in the magisterial Oxford English Dictionary ("the definitive record of the English language") confirms the Māori origin of the word, and notes its varied pronunciations -- and ways it has been spelt -- when used in English:

manuka, n.

Pronunciation: Brit. /mə'nuːkə/, /'mɑːnəkə/, U.S. /mə'nukə/ , /'mɑnəkə/, New Zealand /'mʌːnukʌ/, /'mʌːnəkə/, /mə'nuːkə/

Forms: 18 manook, 18 manouka, 18 manuca, 18 manukau, 18 menuka, 18 minuka, 18– manuka. Also with capital initial.

Frequency (in current use): [This word belongs in Frequency Band 3. Band 3 contains words which occur between 0.01 and 0.1 times per million words in typical modern English usage. These words are not commonly found in general text types like novels and newspapers, but at the same they are not overly opaque or obscure.]

Origin: A borrowing from Maori. Etymon: Maori mānuka.

Etymology: < Maori mānuka, denoting both red manuka and white manuka (the latter is also called mānuka rauriki).

New Zealand.

Either of two evergreen Australasian shrubs or small trees of the family Myrtaceae, with very hard, dark, close-grained wood and with leaves which are sometimes used as a substitute for tea: (a) (more fully red manuka) Leptospermum scoparium, with reddish wood, found in Australia as well as New Zealand (also called red tea-tree); (b) (more fully white manuka) Kunzea ericoides, with small white flowers, endemic to New Zealand (also called kanuka, white tea-tree). Also: the wood of such a plant; scrub composed of such plants. Frequently attributive.

The first three citations following the Oxford definition also illustrate three of the most common ways of referring to the plants concerned: the English name tea-tree, and the Maori words mānuka and kahikātoa), all of which were in use by English-speakers in the first half of the 19th Century:

c1826–7 J. BOULTBEE Jrnl. of Rambler (1986) 110 Tea tree bush—mánook.

1832 London Med. Gaz. 18 Feb. 750/1 This tree..is probably a species of Leptospermum. It is found abundantly at New Zealand,..and is named Kaeta~towa, or Manuka, by the natives.

1840 J. S. POLACK Manners & Customs New Zealanders II. 258 This wood, called by the southern tribes Mánuka, is remarkably hard and durable.

(The citation from Pollack is taken from his description of the kahikātoa).

The word ranked well above "Band 3" in its frequency in the Māori-language newspapers published between around 1840 and 1920, making the first of several hundred press appearances in Te Karere o Nui Tireni for 1 August 1842 (Vol. 1, No. 8, p. 31) in an account of the apprehension of a chicken thief "i nga huruhuru neke atu ko te hutinga i roto i te manuka" [among the scrub heading for a clearing in the mānuka]. In the Wellington corpora of written and spoken English (each database containing 1 million words), research for which was completed in 1990, there were 16 occurences of 'manuka" in the spoken corpus and 12 in the written.

Mānuka is thus a Māori word used in New Zealand English and internationally to refer to New Zealand plants currently or until recently included in the species Leptospermum scoparium, and the honey collected from bees which have visited such plants. The New Zealand varieties of Leptospermum scoparium s.l. are not identical with the Australian ones; even some South Island plants which are similar to a Tasmanian strain differ from the latter in having wider leaf bases and more pungent leaf tips than their Tasmanian counterparts, and, very importantly, they lack the lignotubers (woody growths around the base of the tree, from which new growth can emerge after the top of the plant is damaged) which the Tasmanian plants have developed as a defence against fire. It is probable that more research will establish that the New Zealand Leptospermum varieties constitute together several endemic species, genetically distinct from the Australian varieties currently grouped with them, with several variants, including the recently re-named Leptospermum hoipolloi f. incanum (formerly L. scoparium var. incanum) and the newly (2021) named L. repo. As with the Kunzea ericoides complex, it is now clear that their subdivision into several distinct species will also be justified. The key point is that it is already also clear that all varieties of Leptospermum native to Aotearoa are endemic (unique to this country).

Mānuka in proverbs and poetry

More often than not, references to "mānuka" in sayings, songs and poems probably refer primarily to mānuka in the guise of kahikātoa, "red mānuka", but others are vague enough to apply to the Kunzea and Leprospermum species, mānuka whānui, equally aptly. One of the latter category is this delightful play on words:

Haere ki Ō-te-rangi-pā-karu ki te kai pua mānuka. [M&G #282]

Literally, "Go to Ō-te-rangi-pā-karu to eat mānuka flowers (or seeds)", which is pretty meaningless, but (remembering that mānuka can be trouble itself as well as a source for making weapons to cause trouble)

if slightly rearranged and re-interpreted as:

Haere ki Ō-taringa-pakaru ki te kai pua mānuka

it becomes "Go to Your-broken-ears to eat the seeds of trouble" ~ that is, ignore what you've been told at your peril!

The Ngati Whatua saying Ko te whare mānuka (M&G #1627), literally "The house of mānuka", stands for an armoury of spears, that is, a formidable bastion. Like the Roman fasces, even the thinner branches of mānuka used for making brooms are extremely strong when bound together, hence the whakatauakī:

Whakapūpūtia mai ō mānuka kia kore ai e whati.

Cluster the branches of the mānuka so they will not break. [M&G 2651]

That is, unite rather than go off in different directions

NM 37, 3 In "He Waiata nā Parearoha" (Nga Mōteatea 37, l.3) there is a reference to puia mānuka -- groves of Mānuka, providing bowers where tūrehu, the fairy folk, gather. Other references to mānuka, however, are less benign. In "He oriori mō Tu-Maunga-o-te-Rangi" (NM 209, line 83), the listener is warned:

Kei hē rā koe te whana kai mānuka

[And be you mindful of the mānuka-armed band]

that is, "Beware of those formidable foes who will be lying in wait for you".

Soot from mānuka was a key ingredient in the dye used for tā moko (tatooing). Mānuka wood was also excellent for smoking meat and fish (a use which is still commercially significant). In days gone by, as well as for fish and birds, it was used for smoking heads of defeated enemies as trophies; an instance of which the composer of "He tangi mō Te Whao rāua ko Tu-poki" wishes to avenge:

Wāhia i waenga i te angaanga

O Ngati Mahuta, nāna te wahine,

Tō kiri pīataata kia whakapakia

Ki te ahi mānuka, ē.

[Go and split wide open the head

Of a Ngati Mahuta, because of their woman

Who has smoke-preserved your shining face

In the mānuka fire, alas.]

[NM 293, lines 11-14]

Mānuka honey

Mānuka honey is a uniquely New Zealand production with important medicinal and gastronomic qualities, which from being a common everyday local product has in recent years become a premium foodstuff commanding very high prices on the world market. The way the honey is produced also ensures that it is certified in a way that ensures geographic and compositional integrity. The burgeoning popularity of manuka honey has made life hard for some beekeppers -- strict standards have been imposed regarding the use of the name; blended honeys must be identified as such, and not sold as "manuka" without qualification, and the prices beekeepers obtain domestically for other kinds of honey have decreased sharply as the price of mānuka honey has soared.

Grading of genuine mānuka honey is done by means of determining the presence of the Unique Manuka Factor (UMF) in the honey and assigning a UMF number ranking its strength. This number represents the unique signature compounds characteristic of this honey which ensure purity and quality. These include: the key markers of Leptosperin, DHA and Methylglyoxal.

Honey produced from NZ mānuka honey was known to possess certain anti-bacterial and healing properties above and beyond those of other kinds of honey, but the source of these properties evaded discovery until breakthrough research by German scientists isolated the presence of the compound methylgloxal (MG) in the honey. It was then found that this is the result of the presence of the compound dihydroxyacetone (DHA) in the nectar of New Zealand plants of Leptospermum scoparium. The strength of the UMF in mānuka honey is mainly proportionate to the MGO content.

The relationship between DHA and Methylgloxal is well explained on the Analytica Laboratories website:

In 2009, scientists at the University of Waikato (Christopher Adams, Merilyn Manley-Harris and Peter Molan) published research that showed that the methylglyoxal in New Zealand manuka honey originates from the chemical compound dihydroxyacetone (DHA), which is present in the nectar of manuka flowers to varying degrees. (Some manuka plants have more DHA in their nectar than others.)

This research found that “nectar washed from manuka flowers contained high levels of dihydroxyacetone and no detectable methylglyoxal.” Furthermore, “manuka honey, which was freshly produced by bees, contained low levels of methylglyoxal and high levels of dihydroxyacetone. Storage of these honeys at 37 degrees Celcius led to a decrease in the dihydroxyacetone content and a related increase in methylglyoxal.”

(Follow the links above for more information).

Leptosperin is a naturally occurring chemical, found only in the nectar of Manuka plants (and a few very close relatives). Its presence in addition to the DHA and Methylgloxal helps assure the authenticity of honey labelled as "mānuka". A few other species of Leptospermum (by no means all) may express leptosperin in their nectar, but these are not grown in New Zealand and so are irrelevant in respect of mānuka honey. It is possible that some New Zealand Kunzea plants may also have minute traces of leptosperin in their nectar (although the evidence for this is weak), but in quantities so small that it would be below the minimum level on the UMF scale.

Early in 2018 Manuka honey producers secured approval from the New Zealand Commissioner of Trade Marks for registering the term "Manuka honey" and prohibiting its unauthorized use. This was reported in the Interest Rural News for March 22, 2018:

IPONZ Assistant Commissioner of Trade Marks Jane Glover stated in her decision, “Regardless of the surrounding legislative framework (which can change), from a trade mark perspective, I am comfortable that for New Zealand consumers at the relevant date, the mark MANUKA HONEY was apt to differentiate leptospermum scoparium honey produced in New Zealand from leptospermum honey produced elsewhere.”

Not surprisingly, some Australian beekeepers would like to take advantage of the burgeoning demand for "mānuka" honey, and apply the name to honey from their own Leptospermum species. It is to be hoped that the Australian authorities will eventually agree that the origin and meaning of the word "Mānuka" would make its application to Leptospermum (or any other) honey produced outside New Zealand inappropriate, and instead decide to treat the word as a New Zealand equivalent of "champagne". Litigation on the use of the word mānuka (however spelt) in connection with honey not produced and certified in New Zealand continues in Australia and the United Kingdom.

|