TE MÄRA REO |

|

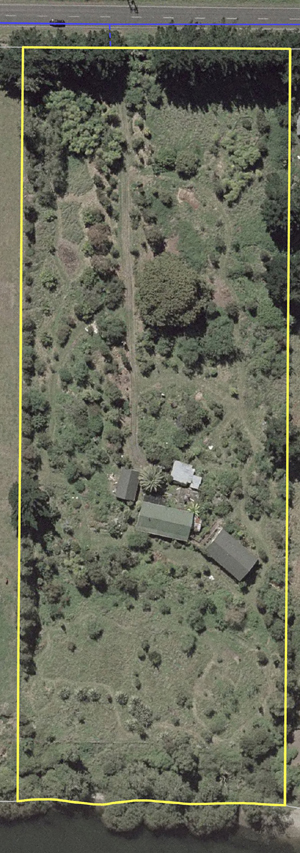

2006 Aerial view of "Tumanako"

2006 Aerial view of "Tumanako"

site of Te Mära Reo

Te Mära Reo - The birth of the idea

A few years ago, some friends were asked to submit ideas for the development of green space in a new town centre being planned for one of our major cities, and asked me what I would suggest. My answer was "Why don't you develop a language garden?" I thought that this was a wonderful chance to educate New Zealanders about a dimension of their native environment that is often overlooked. My suggestion was that as many as possible of the New Zealand native plants bearing names that were brought here from Polynesia by the first settlers should be grown in a rough order of the antiquity of the name, and that where plants bearing cognate names in other parts of Polynesia could be grown (either in the open or, for example, in small conservatories scattered through the other plantings), these should be included too. All the plants should be accompanied by informative labels. That way people wandering through the garden could get a feel for the origins of our plant names, and also get to know some of the plants from other parts of the Polynesian and wider Austronesian worlds that share their names with ours.

Some of the people on the planning committee liked the idea, but the developers thought it would be difficult to organize, and might take up too much space that would better be used by buildings. "However," my friends said, "you've already got half the plants here -- why don't you just do it yourself!" I laughed at this at first, but when I looked at the records of what we had planted over the preceding decade, and checked this against a list of inherited plant names, I saw that my friends were probably right, and decided to rise to the challenge. It was a logical extension of what my late wife, Nena, my son James and I have been doing here since coming to the Waikato in December 1996. When we arrived, our newly acquired 2 hectare property consisted of completely bare paddocks, surrounded by 110 pine trees around the boundary, including a dozen along the driveway, apart from a single, large oak tree about 75 metres from the gate, and a phoenix palm and a virgilia, along with a few seedling trees and shrubs, near the house. The virgilia and all the pine trees, except for two which have been topped, have now been felled, replaced by 50 kauri trees and hundreds of other New Zealand native trees, along with trees to supply nectar to the birds, fruit trees to feed us (and them!) and some ornamentals. We called the place "Tumanako" ["hope"], trusting that it would come to be a refuge which embodied the hope of a sustainable and environmentally sensitive and secure future.

So, inspired rather than disappointed by the initial rejection of our idea, we have begun developing and documenting a “language garden” on our Ngaruawahia land, with the aim eventually of growing there as many as possible of the 130-odd species of native plants whose names were brought here by this country’s first Polynesian settlers. In the very near future, we hope to be able to welcome small numbers of interested visitors and school groups to see the plants and learn about the history and relationships of their names. We have already had a few successful "trial runs" of a "time travel" tour, and a small brochure for people doing the 800 metre hike. One of these visits was reported in the May 2010 issue of the Waikato Botanical Society's Newsletter (click here to read it). Some of the stories of these plants will be told in the entries relating to each of them in these web pages (see the side-panels for links to the individual entries), and information about the plants with related names elsewhere in Polynesia and further afield is also given in these pages and in a separate set of pages for the words which the contemporary names can be traced back to. On those pages I will also give accounts of the "namesake" plants that I have seen myself as I have encountered and photographed them in other parts of Polynesia. I'll also eventually write guides to different stages in the history of the names, linked to the plants both in the garden and those noted in these pages (e.g. "canoe" plants that were carried from place to place by Polynesians and their Austronesian forebears as they set out to colonize new lands), so new options will appear in the side panels on this and some other pages ä te wä [in the fullness of time].

Although there will be a lot of factual and scholarly information in these pages, there will also personal opinions, accounts and speculations which, while hopefully reasonably well-grounded, are essentially matters of opinion and might be quite wrong (not that generally accepted "facts" and scholarly findings are always right, either, of course!). This website will always be "work in progress", but hopefully the gaps will be fewer as time passes. We will give priority to accounts of plants that we have growing in the garden, and to those whose Maori names have Hawaiian cognates (because I spent a couple of months in Hawaii in 2007 studying these); however, eventually all the plants listed in the "index" will have a page with some information about their Aotearoan referents, and another about the word that their current name originated from, whether they happen to be growing in our physical garden or not. That's the advantage of operating in cyberspace.

The header line at the top of each page includes a small picture of one of our resident pïwakawaka (fantails, Rhipidura fulginosa) -- friendly, talkative little birds who were here to greet the first human arrivals. The footer contains a picture of the flower of the hue (calabash gourd, lagenaria siceraria), a plant that was brought here by the first East Polynesian settlers and still grows excellently in our garden (I was very pleased to see that, despite the less favourable climate, our plants looked much more vigorous and happy than their Hawaiian counterparts that I encountered when I was in Hawaii last year). Clicking on either of those images on another page will bring you back to this one. There is also a "creative commons" copyright notice at the foot of each page which grants permission for non-commercial use of this material provided that its source is acknowledged.

Richard Benton

Director, Te Mära Reo

April 2008

Te Mära Reo is affiliated with the International Eco-Tourism club, Eco Club: http://www.ecoclub.com/, and the "Willing Workers on Organic Farms" organization, WWOOF New Zealand: http://www.wwoof.co.nz/ |

Te Mära Reo, c/o Benton Family Trust, "Tumanako", RD 1, Taupiri, Waikato 3791, Aotearoa / New Zealand This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 New Zealand License. |